- Home

- Shiro Hamao

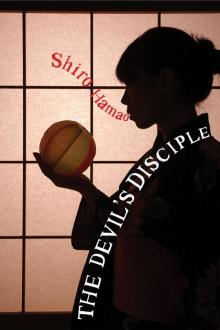

The Devil's Disciple

The Devil's Disciple Read online

Hesperus Worldwide

Published by Hesperus Press Limited

19 Bulstrode Street, London W1U 2JN

www.hesperuspress.com

‘The Devil’s Disciple’ was first published in Japanese as ‘Akuma no deshi’ in the April 1929 issue of Shinseinen.

‘Did He Kill Them?’ was first published in Japanese as ‘Kare ga koroshita ka’ in the January and February 1929 issues of Shinseinen.

This collection first published by Hesperus Press, 2011

Introduction and English language translation © J. Keith Vincent, 2011

Designed and typeset by Fraser Muggeridge studio

Printed in Jordan by Jordan National Press

ISBN: 978-1-84391-857-8

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not be resold, lent, hired out or otherwise circulated without the express prior consent of the publisher.

Contents

Introduction

The Devil’s Disciple

Did He Kill Them?

Glossary

Biographical note

Note on Japanese Name Order

In this volume, Japanese names are given in the Japanese order, with the family name first followed by the given name. For example: ‘Hamao Shirō’.

Introduction

Hamao Shirō’s career as a writer of detective fiction lasted only six years before his tragically early death at the age of forty. During that time he produced sixteen novellas and three full-length novels, leaving a final one unfinished. The stories included here are the first two he ever published, both in 1929, in the pages of New Youth, a wildly popular magazine that promoted the heady brew of aestheticised decadence, gothic horror, and pseudo-scientific sexology and criminology known in 1920s Japan as ero-guro-nansensu or ‘erotic grotesque nonsense’. Like most of the work written under this banner, these early stories have a noir-ish feel that some readers may find a little dated and, perhaps a lot, over the top. But they are still very much worth reading despite these flaws, I submit, for the window they offer into interwar Japan, for the provocative questions they pose about sexuality, justice and the law, and – last but not least – for a certain campy sensibility that is perhaps not surprising given that Hamao was also one of Japan’s earliest apologists for male homosexuality.

Hamao Shirō (1896-1935) was born into one of modern Japan’s most powerful families and married into another. His grandfather, Baron Katō Hiroyuki, was a conservative legal scholar who gave lectures to the Meiji Emperor and served twice as the President of Tokyo Imperial University. His father was Baron Katō Terumaro, a member of the House of Peers and a prominent physician in the service of both the Meiji and Taisho Emperors. In 1918 Shirō married the daughter of Viscount Hamao Arata, another past president of Tokyo Imperial University and a founder of the Tokyo School of Fine Arts. Upon Arata’s death in 1925, Shirō, who had already taken the Hamao name, inherited the title of Viscount. It was also in this year that he was appointed as a public prosecutor in the Tokyo District Court at the young age of twenty-nine.

He did not remain a prosecutor for long, however. Within three years he had resigned his position, opened a private law practice, and begun a new career writing detective fiction. His society friends were no doubt aghast that he had given up this prestigious position in order to write in such a lowbrow genre, but Hamao had decided that rather than trying to follow in the footsteps of his grandfather, who had helped create the modern Japanese legal system, he would use his talents to write fiction that would critique it. His work as a prosecutor had served only to disillusion him with the workings of the law and to confirm the critical insider’s perspective his upbringing had given him on the upper echelons of government and the legal profession. Detective fiction was a way to work through that disillusionment and to explore the fallibility of the law. At the same time, as the first detective novelist in Japan to have a law degree and experience as a prosecutor, he was able to bring a degree of legal expertise to his work that was sorely lacking in most detective fiction in Japan at the time. Both of the stories translated here deal with this theme of the law’s fallibility, as does the only other story by Hamao published thus far in English, ‘The Execution of Ten’ichibo’, beautifully translated by Jeffrey Angles in volume 32, issue number 2, of Critical Asian Studies (2005).

Pre-war Japanese detective fiction typically fell into one of two categories. In the ‘orthodox’ (honkaku) variety the detective identifies the culprit through brilliant feats of reasoning and, by solving the mystery, repairs the damage the crime has done to the social fabric. In this variety the narrator tends to have a dependably objective and unbiased perspective and refrains from playing tricks on the reader. This relatively reassuring and socially conservative form was the norm in Japan beginning in the 1880s with the translation of authors like Arthur Conan Doyle and Émile Gaboriau. It was not until the 1920s, however, with the introduction of the ‘heterodox’, or henkaku style, that detective fiction really took off in Japan. In heterodox detective fiction, which traces its roots both to Edgar Allan Poe and to writers of ‘pure’ literature such as Tanizaki Jun’ichiro and Akutagawa Ryunosuke, the narrators are not as reliable, and while the crime may be ‘solved’ the reader is far from reassured. While orthodox detective fiction tended to draw clear distinctions between guilt and innocence, good and evil, in the heterodox form these lines became deliciously blurred.

Hamao’s work encompassed both orthodox and heterodox elements. In his longer works, such as Satsujinki (The Murderer), 1932, which was loosely based on S.S. Van Dine’s 1928 novel The Greene Murder Case, the emphasis was on ‘whodunit’. As in Van Dine’s novel, the plot of The Murderer was so tightly constructed and the culprit so brilliantly concealed that Hamao’s friend and fellow detective novelist Edogawa Ranpo praised it as a model of the orthodox form. And yet even in this most orthodox of his novels, Hamao showed heterodox tendencies that distinguished his work from that of Van Dine. Whereas Van Dine’s detective Phylo Vance was a Holmes-like figure, preternaturally clever and pedantic, Hamao’s detective Fujieda Shintarō relied on emotional intelligence and intuition.

In the two novellas translated here, Hamao clearly prefers the blurrier ground of the heterodox. There is no detective protagonist in either, nor is the focus precisely on the ‘solving’ of a crime. Questions of guilt or innocence matter less than the exploration of psychologically complex motives. In ‘The Devil’s Disciple’ the narrator is an accused murderer writing a letter to his ex-lover who happens to be a prosecutor in the court where he is being tried. While he insists on his innocence of the crime he is accused of, his narrative is motivated less by a desire to prove it in a court of law than to blame the prosecutor for everything that has gone wrong in his life. In the process, he projects what seems to be his own homophobia and misogyny onto his former lover and also onto the legal system that he represents. In ‘Did He Kill Them?’ the narrative takes the form of a speech given by its barrister narrator to an audience of detective novelists, a conceit that allows Hamao to explore on a meta-fictional level the differences between his own brand of detective fiction and that practised by the orthodox school. In both stories scepticism about the law is delivered with an equal dose of scepticism about the reliability of narrators. In ‘The Devil’s Disciple’ the narrator’s obsessive, homophobic rancour toward the prosecutor makes it impossible to know how far to trust what he says, and the story offers us no external perspective from which to judge. In ‘Did He Kill Them?’ the narrator lacks the paranoid intensity of ‘The Devil’s Disciple’ but the story still plays with the effects of (homo)sexual attraction on legal and narratorial objectivity.

When the narrator of ‘Did He

Kill Them?’ states matter-of-factly that he is ‘a man who is quite capable of appreciating a good-looking youth’, he is probably expressing the author’s tastes as well. Hamao had a scholarly and perhaps also a personal interest in male homosexuality that makes itself known in more or less subtle ways in most of his work. Ranpo called him ‘my teacher on the subject of homosexuality’ and, like the prosecutor Tsuchida in ‘The Devil’s Disciple’, he was well versed in the work of European homophiles and radical sexologists such as Edward Carpenter, Karl-Heinrich Ulrichs, Magnus Hirschfeld, and Havelock Ellis. While sex and love between men was widely accepted and even celebrated in premodern Japan, by the 1930s modern sexology and psychiatry had recast it as a pathology and a perversion. Hamao was one of the first writers to oppose this. In 1930 he published an essay in a women’s magazine in which he argued that homosexuality was not an illness but an innate aspect of personality. After the article came out he received a flood of letters from closeted ‘urnings’ (Ulrichs’ term for men loving men) all over Japan who described the pressure their families put on them to marry, their sense of shame about their homosexuality and their fear that it should be revealed. In response to these letters Hamao wrote another article in the same magazine addressed to all of Japan’s ‘urnings’ in which he encouraged them not to be ashamed and called for a greater understanding and tolerance. With this letter Hamao became one of Japan’s first modern advocates for what would later be called ‘gay rights’. While in this sense Hamao was very much ahead of his time, it is worth noting that his attitude had as much to do with his access to a cultural memory of a less homophobic past as it did with his anticipation of a more liberated future. One of the most fascinating aspects of ‘The Devil’s Disciple’ is the way it captures a moment of historical overlap between two different ‘regimes’ of sexuality by giving us a nostalgic view of a still normative schoolboy homosexuality in the past seen through the lens of an increasingly paranoid and homophobic present.

Note

As the reader will soon discover, the game of mahjong plays an important role in ‘Did He Kill Them?’. Hamao himself was a great fan of the game. He served as president of the Tokyo Mahjong Society and even had a special room reserved for mahjong in his house. For these reasons it was crucial to achieve an accurate translation of the mahjong game and, not being a player myself, I was very grateful for the help of my friend Kitamaru Yūji in the translation of those passages. I would also like to thank Martha Pooley of Hesperus Press for her infinite patience and brilliant editing.

The Devil’s Disciple

I

Mr Tsuchida Hachirō, Esq.

Prosecuting Barrister at the XX District Court

I, Shimaura Eizō, a prisoner awaiting trial, have taken the liberty of sending this letter to you, Prosecutor Tsuchida, my erstwhile friend who was once more dear to me than a brother.

You do remember me, don’t you Mr Prosecutor? My case may have been investigated by another prosecutor and landed on the desk of another judge, but as the accused in the sensational murder of a beautiful woman, no doubt my name has been all over the newspapers. Since you work in the same court in which I am being tried you could hardly have failed to notice my name in connection with this case. You must have heard of it.

If you had agreed to meet me I might have been spared the writing of this letter. If I had remembered earlier that my old friend was serving in the court attached to the very prison in which I am being held, I might not have had to suffer as long as I have. I might have been able much earlier to relate the bizarre experiences that I am about to set down here.

Prosecutor Tsuchida, I am being held here as a murderer. But the truth is that I am probably not that murderer. That’s right. Probably. It saddens me to have to say this. And I apologise for expressing it in such an odd way. But if you will be so kind as to read this letter through to the end I promise that you will understand.

The horrific things I am about to describe are not entirely without relation to you. In fact it is fair to say that it is you who have made me suffer so. And because of that only you can understand my pain. Part of me hates you for this. I curse you for it. But now I beg you. I bow down before you. In the name of that friendship we once shared, that friendship of unparalleled closeness, I beg of you to believe what I have to say.

II

Let me address you as Tsuchida-san.

I shouldn’t think that would be a problem.

Tsuchida-san, I ask you for a moment to step aside from your imposing profession as a prosecutor and think back to how things were a decade ago. Think back to our student days, when we had just put secondary school behind us and passed the next hurdle to those tearful, torrid days when we lived in the school dormitories.

We were best friends. Actually we were even more than best friends were we not? Was I not always to be seen at your side wherever you were and you at mine, no matter where we went? Were we not known among our dormitory mates as a Paar?

You are three years older than I am. You were the older brother looking for a younger one. I was young – still a child really – and I was overawed by the strength of your personality. Soon I had become your one-and-only little brother. Surely you cannot have forgotten this.

I thought I had found someone who could understand my loneliness. Even better, you were kind enough to love me. On top of that, you were brilliant. I respected you and came to believe that you could do no wrong.

For two years our friendship burned like a flame. The opposite sex was nothing to us. After those two years you graduated and went on to a top university. And what happened to us?

We split up all of a sudden. All too suddenly. And after that we barely saw each other again. Tsuchida-san, you, of course, were the cause of our break-up. You left me because you fell passionately in love with a beautiful boy one year below me in school.

Did you ever deign to ask yourself how your younger brother felt after you so carelessly tossed him aside out of fickleness?

I thought we loved and understood each other. I thought our friendship would last forever. But you stopped caring and left me all alone. I looked hard at myself from within that loneliness. I saw myself quite clearly there, and the self that I saw had no choice but to revile and curse you.

Self-absorbed as you are, you will no doubt interpret whatever I say to your own advantage.

Your face will contort into that devilish smile of yours as you picture to yourself a woman abandoned by her lover and despising him for his cruelty. But that’s not what was going on at all. I had other reasons to hate you.

So yes, we were lovers of a sort. And I was forsaken by my lover. But getting away from you allowed me to take a good look at myself and at you as well, all the way through you.

Tsuchida-san. You are the most dangerous person in this world.

You are a devil. Devouring the flesh of humans is not enough for you. You are a hateful devil who won’t stop until you have cast their very souls into hell.

You were a brilliant prodigy. You had an intellect of rare penetration. (And I suspect you still do.) But with that brain and that eloquence what did you do to the young men who gravitated toward you? What did you teach them? Have you, at least in my case, ever given a thought to how you warped their personalities?

You spoke with passion and preached with tears. The most irrational ideas sounded rational on your lips. The most specious rhetoric sounded utterly logical when it came from you. But what was it all in the end? Did it not end by destroying every pure soul that came near you?

When I first met you I was an innocent boy. By the time we parted, alas! I was the disciple of a devil.

You used to say to me, ‘Life is not a rose-strewn path. It is a battle and we must fight.’

But it was not the battle that excited you. It was destruction. The lust for destruction. You loved to destroy things. You weren’t happy until you had brought pain and suffering to the boys who loved you, until you had brought them low. But you

yourself never fell. That is what made you so frightening, so dangerous.

You love to give alcohol to boys who don’t know the taste of liquor and then sit back and watch them suffer. But you don’t stop there. You want to watch them as they fall further and further into alcoholism while you yourself never touch a drop.

If you were just a hard-drinking, whore-buying ruffian you may not have posed such a danger. Why? Because you would have been the object of universal contempt. But everyone thought of you as a perfect gentleman (despite the fact that in your case a certain distance from the fair sex was hardly indicative of virtue). This is what made you so dangerous. Those naive and good-hearted boys all trusted you. They became your disciples. And what became of them? Tsuchida-san, I know young men besides myself who were loved by you. And I know how they ended up.

I gained knowledge, but sold my soul. I will have to live with the fact that I sacrificed my body to your strange love, but having sold my soul fills me with regret.

Tsuchida-san, I’ve allowed myself to voice this bitterness for too long already. There really is no end to this kind of complaint. As I mentioned before, I have not begun this letter in order to criticise you. So let me get to the point.

III

I am not blaming you, but I want to make one thing clear, and that is how much my personality changed because of you.

When I first met you in the grounds of our school I was a vulnerable young boy who wouldn’t hurt a fly. But you remember all the horrifying stories you told me every time we met. Before then I’m sure I was completely uninterested in horror, in the bizarre or the criminal. But you found it fascinating to the extreme and introduced me to literature and scholarly works on all of these subjects. Thinking back to it now I see that what you really liked was forcing your own tastes on me and making me drink that poisoned brew. But I knew nothing of this. I trusted you and believed everything you said.

The Devil's Disciple

The Devil's Disciple